July 14, 2023

Learn To Fly Safety Corner July 2023 – Incident Trend Analysis

At Learn To Fly Melbourne, our Safety Management System (SMS) conducts incident analysis to identify developing trends as part of its safety risk management process.

Incident analysis carried out over the past 3 months (April to June 2023) has identified aircraft separation issues as an emerging risk.

Recorded Incidents Include:

- Near collisions. Serious near collisions between aircraft, including instances where the crews of both aircraft did not see each other until moments before or after, the aircraft’s flight paths crossed.

- Evasive manoeuvres. Pilots have to manoeuvre to maintain/increase separation from other aircraft not complying (or not able to comply) with traffic sequencing instructions.

- Communication difficulties. Pilots are not able to comply with traffic sequencing instructions, not communicating their intentions or actions.

- Operational non-compliance. Pilots inadvertently do not (or are not able) to follow/maintain traffic sequencing instructions (cutting aircraft off in the circuit).

- Separation standards. Pilots not maintaining sufficient separation with preceding aircraft leading to forced go-arounds.

- Frequency management errors. Pilots reporting ready on the wrong frequency leading to aircraft entering the wrong runway for take-off.

- Approaches to the wrong runway. Pilots confusing Runway 13 Right (RWY 13R) for RWY 17R.

- Runway incursions.

Air Traffic Control (ATC) errors. Controllers are late in passing traffic to aircraft and applying inadequate take-off and landing separation standards.

Contributing factors

The limitations of the see and avoid principle;

The complexity of Moorabbin Airport’s runways and procedures;

Traffic volumes at Moorabbin;

Traffic density in the circuit;

The pilot workload in the circuit;

The number of student solo flights operating at Moorabbin with the minimum, but limited levels of experience;

Human factors issues.

Countermeasures

Unless their aircraft is fitted with an ADSB transponder and traffic avoidance technology, pilots will have only the traditional collision avoidance techniques to maintain separation from and avoid other aircraft.

The following pilot skills and knowledge will reduce the risk of aircraft separation issues identified in LTF’s trend analysis.

Maintain an Effective Lookout

It’s crucial that pilots maintain an effective lookout, backed by a thorough understanding of the limitations of the “see and avoid” principle. An effective lookout involves a systematic visual scan of the surroundings, cognizant of factors that might diminish the chances of spotting and accurately interpreting visual targets.

An integral part of this is understanding the physiology of the eye. Visual acuity, for instance, which relates to how well one can see based on the size of and distance from a target, is a fundamental component. So too is one’s field of view and the limitations of peripheral vision, particularly when it comes to distinguishing between moving and stationary targets.

Adapting to shifting light levels (such as from cloud shadows) and the time it takes to refocus from internal to external cockpit references are other key considerations. This also includes understanding the impact of empty field myopia – the eye’s default focus distance when peering into a seemingly endless sky.

Keep in mind that an aircraft maintaining a constant speed on a converging flight path can appear stationary to the crew of both planes. This relative movement, or lack thereof, can skew perception. It’s also important to note that human perception can be limited due to factors like illness, medications, or fatigue.

Environmental conditions can also make visual identification challenging. This includes the clutter of visual background (like an aircraft below the horizon), light levels, sun glare, and the position and elevation of the sun compared to the visual target. Even the visibility offered by the atmosphere plays a role.

Aircraft ergonomics, such as door posts, window sizes, and frames, along with the presence of other crew members, can obstruct vision. The design of the aircraft’s airframe, including the nose’s position relative to attitude and high-wing versus low-wing designs, can also limit visibility.

Also, never underestimate the effect of more straightforward factors, like the contrast between the aircraft’s colour and its backdrop, and the cleanliness of the windscreen. Each of these aspects plays a crucial role in minimising the risk of aircraft separation issues. So, next time you’re in the cockpit, remember to incorporate these principles into your routine scanning techniques to ensure safe and effective flights.

Maintain a Listening Watch

Alerted see and avoid greatly increases the likelihood for pilots of seeing other aircraft. Accurate radio communication identifying an aircraft’s location, altitude and intentions improves the opportunity to see an aircraft by knowing where to look rather than having to scan the whole sky. Information about where to look for an aircraft and where it is going may be included in the following:

- Aircraft position reports and readbacks;

- Pilots are broadcasting their intentions;

- ATC instructions;

- ATC traffic advisories and alerts.

Effective Communication

In the dynamic environment of aviation, clear and concise communication of your actual position and intentions is paramount. However, situations may arise when things don’t go as planned – you may find yourself unable to comply with an instruction, not understanding an instruction, unable to spot the aircraft you should be following, or unable to accept an instruction. There could also be circumstances when it’s simply not safe to comply with an instruction.

In such instances, it’s essential to communicate your situation to Air Traffic Control (ATC) promptly and accurately. Whether it’s about your inability to adhere to a directive, uncertainty about an instruction, or your inability to visually locate another aircraft, clarity is key.

Do not hesitate to voice your situation. Even if you’re unsure about the standard phraseology, opt for plain English to convey your message. The goal is to ensure that ATC fully understands your situation and can provide the appropriate guidance or alternative instructions to help maintain the safety and efficiency of your flight operations. Remember, effective communication forms the backbone of aviation safety, especially when dealing with unexpected situations in the air.

Expect the Unexpected

Humans are prone to making errors, and pilots are human, so, inevitably, pilots of other aircraft will not operate their aircraft as expected on occasion. Provide a margin for safety so that errors made by pilots of other aircraft or deviations from expectations do not impact your aircraft’s safety.

- Check for aircraft on approach to land when you are cleared for take-off by ATC.

- Look out behind for aircraft that could turn early and cut you off on all legs of the circuit.

- Be prepared to go around in case the landing aircraft ahead of you experiences difficulties.

- Lookout for aircraft or vehicles along the full length of the runway.

- Aircraft experiencing difficulties may not be able to operate as they normally would.

Flying predictably improves the opportunity for aircraft to see each other by improving situational awareness. Predictable flying allows other pilots to anticipate where to look to see your aircraft. Fly your aircraft using standard procedures to achieve expected performance, speeds, and the established circuit pattern.

Know Your Aerodrome Procedures

Know your aerodrome operating procedures and the procedures used by helicopters. An understanding of helicopter operating procedures will improve your ability to predict where they will be and your opportunity to see and avoid them.

Helicopter circuit operations occur on the eastern grass when runways 17/35 are operating. The helicopter circuit pattern is inside the aeroplane circuit at 700 feet and is normally close to the airport boundaries.

When runways 13/31 are in operation, helicopters conduct circuit operations from the western triangle, an area south and west of RWY 31 left. Their circuit pattern is on the inside of the aeroplane circuit at 700 feet.

Helicopters arriving from the east either overfly the landing runway threshold not below 500 feet or overfly midfield not below 700 feet for a short western circuit to the helicopter landing areas.

Know the Performance of Your Aircraft and Other Types

Helicopters arriving from the east either overfly the landing runway threshold not below 500

Knowing your aircraft’s performance capabilities compared to other aircraft will improve your ability to predict where they will be in relation to yours and improve your opportunity to see and avoid them.

Multi-engine aeroplanes practising simulated engine failures achieve degraded climb performance and may extend upwind and crosswind legs.

Discuss the performance of other types and categories of aircraft with your instructor.

Human Factors

Human performance limitations and normal human psychological predisposition make pilots prone to error. Human Factors (HF) is the broad study of the risk the human pilot human poses to aviation safety and strategies to minimise the risk. Some examples of HF that may diminish safety include:

- Fixation;

- Distraction;

- Task saturation;

- Stress and anxiety;

- Hazardous personal attitudes;

- Incorrect perceptions and biases;

- Poor setting, poor priorities and decision-making;

- Ineffective communication and relationships with others.

The Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASR) Part 61 (flight crew licencing) Manual of Standards (MOS) Non-Technical Standards (NTS-1 and NTS-2) describe non-technical (human or soft) skills pilots must acquire to minimise the risk of the negative implications of the human component of being a pilot. Things you can do to alleviate human error can include:

- Develop your non-technical skills (situational awareness; assess situations and make decisions; set priorities and manage tasks; etc.);

- Discuss HF with your instructor when planning flights;

- Perform a rigorous IMSAFE assessment before flights;

- Pre-flight preparation and planning help to reduce pilot workload and decrease the likelihood of errors.

Threat and Error Management

Other factors may adversely affect a pilot’s ability to operate safely in the vicinity of other aircraft. Threat and Error Management (TEM) is the process of anticipating factors that may impact the safety of a particular flight. The risk of Treats and Errors can be mitigated with careful pre-flight preparation.

The following threats can impose an additional layer of complexity and impact safety and the opportunity for errors during flight:

- Fatigue;

- Visibility;

- Sun glare;

- Light levels;

- Traffic density;

- Aircraft familiarity;

- Recent experience;

- Aircraft serviceability issues;

- Feeling pressured (external and internal).

Knowing the principles and application of TEM and carefully assessing the likely TEM items that may affect your flight will decrease the likelihood of their having a negative impact on safety.

Your instructor will assist in assessing TEM as part of every solo flight authorisation.

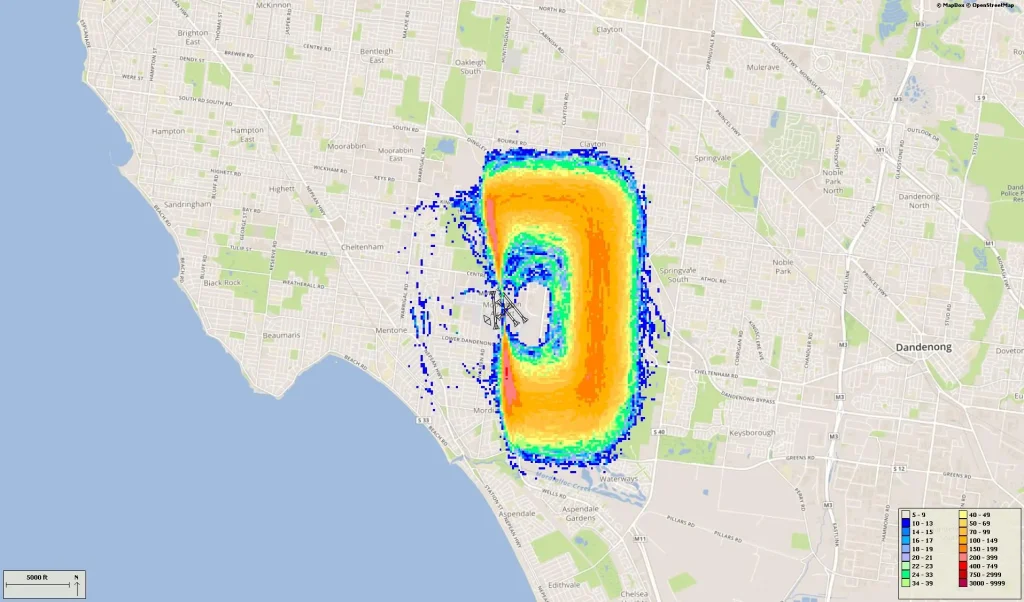

Collision Risk in the Circuit

Collision risk increases in the circuit. The circuit funnelling aircraft to the runway threshold (a fixed point on the ground) in a common traffic pattern based on the runway. The consistency with which the circuit is flown increases the risk of collision between aircraft whose pilots have not seen each other.

Aircraft following you in the circuit likely represent the greater threat. Following aircraft, even slower ones can create a collision risk if they turn early (cut in) on a leg of the circuit. The following aircraft are difficult to maintain visual contact with due to their relative position and aircraft ergonomics. Look behind when down-wind and on base. Look for aircraft on a close or high base when established on final.

There are areas in the circuit with a higher risk of collision. On the final approach, the runway provides lateral and vertical visual cues to permit pilots to fly a more accurate and consistent flight path.

On final, the opportunity to visually acquire aircraft on a converging flightpath will be diminished with the pilot’s attention being strongly focused on the runway to monitor the approach. Make a conscientious effort to look for traffic before joining the final and to scan for traffic throughout the approach to land.

Resources

Resources to assist pilots in developing knowledge to avoid aircraft separation issues.

Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) on Avoiding Collisions

- Limitations of See and Avoid

- Review of Midair Collisions Involving General Aviation Aircraft in Australia between 1961 and 2003

Airservices Australia on Runway Safety

Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) on Collision Avoidance

Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) on Flying Around Melbourne and Moorabbin

Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) on Human Factors

Chat to one of our flight training specialists to get your pilot training off the ground. Email hello@learntofly.edu.au or go to https://drift.me/learntofly/meeting to book a meeting and school tour.